Could Ketamine Cure Tinnitus?

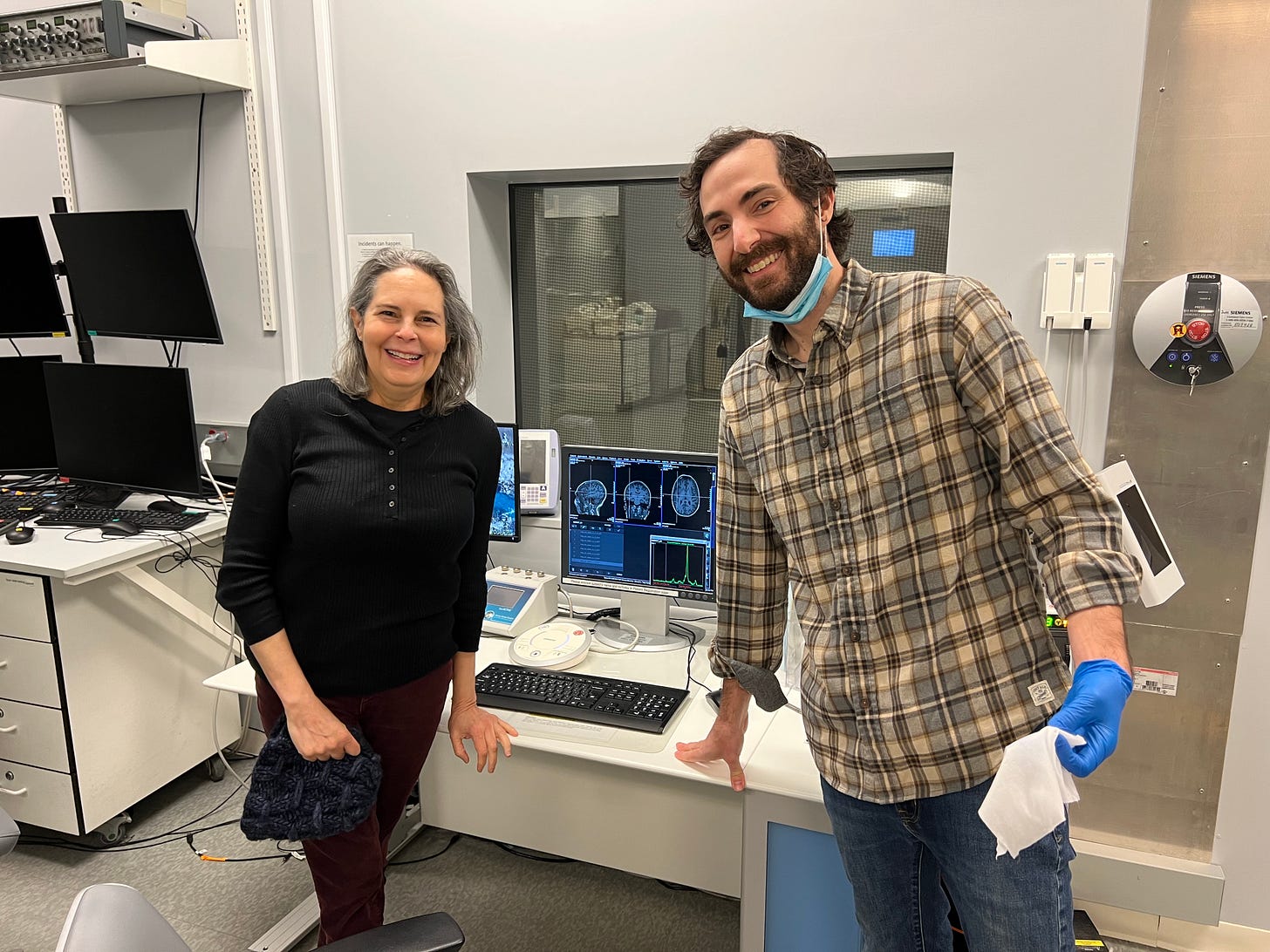

I entered a clinical trial to see if ketamine would stop the constant ringing in my left ear. The catch? I'd have to spend 90 minutes, while tripping, completely immobile in an MRI.

The call to clinical trial, after two years of a high-pitched ringing in my left ear, came via an Instagram ad. Would I be willing to be a data point …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ladyparts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.