It's Never Too Late to Write That Novel

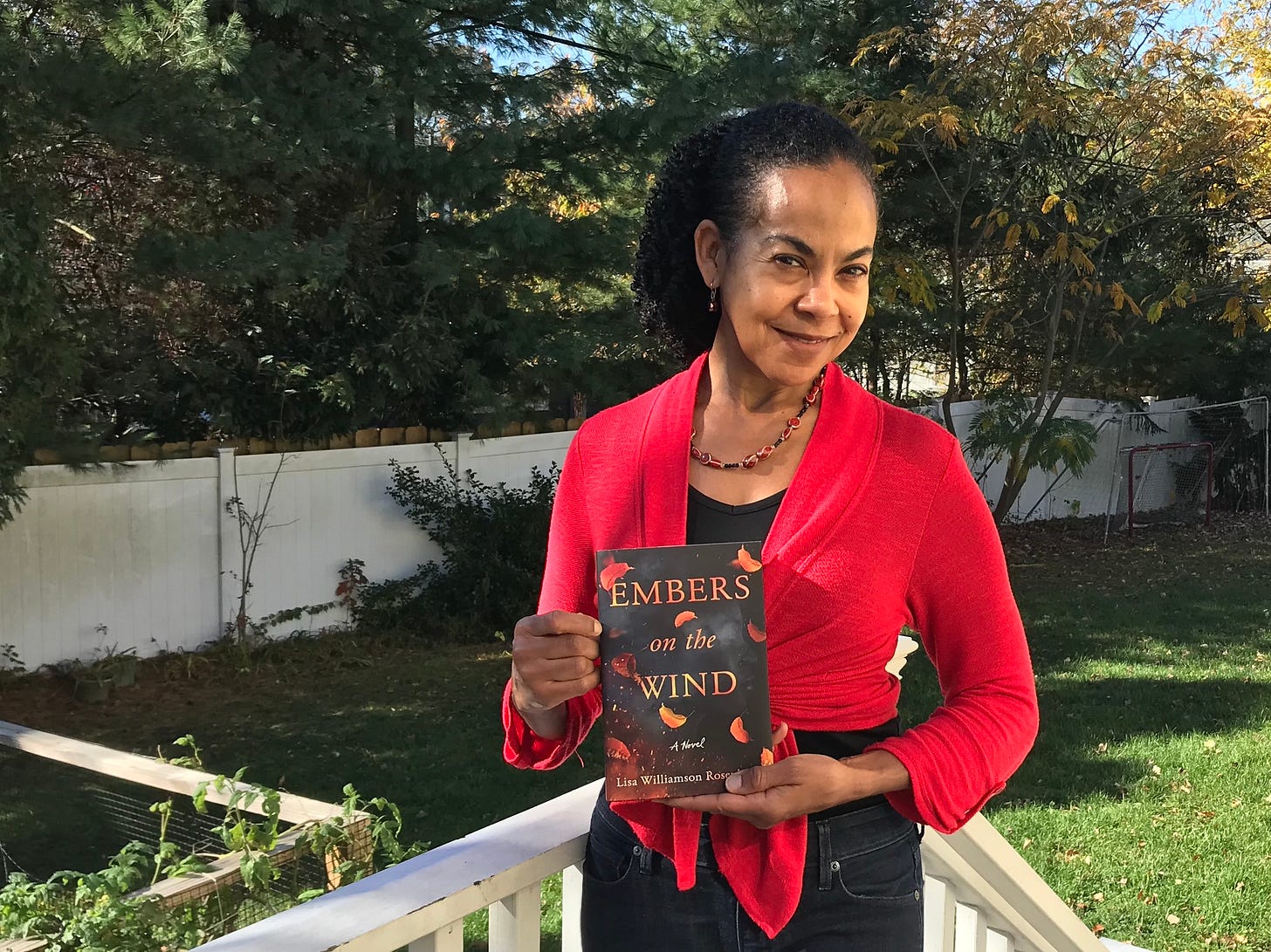

Lisa Williamson Rosenberg has been making up stories since she was three years old. It just took another five decades and a haunted house in the Berkshires for her to nab her first book deal.

Lisa Williamson Rosenberg was three years old when she began dictating stories to her mother. “I went nuts,” she said, “spinning out the adventures of Picky the Penguin and his sidekick Retanya.” While neither Picky nor Retanya ever made it into a published novel—I mean, yet—Lisa hel…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ladyparts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.