Married women: now they're going after your right to vote

Did you change your name when you got married? Do you know where your birth certificate is? If the answer to the first question is yes, the second, no, the SAVE act is designed to suppress your vote.

Back in 2017, I wrote an Op-Ed for The Washington Post about the humiliations and absurdity of having to acquire my ex-husband’s signed and notarized permission to reclaim my birth name in the middle of our extended divorce. If you, like me, cancelled your subscription to the Post when Bezos stuck his nose up our president’s ass1, here is the key paragraph from that essay, and I’ll reprint it in full at the end of this story, should you be in the mood to read the whole thing.

Legally, there’s no statute in my state requiring spousal consent for a name change. Lawyers familiar with name change law were not aware of such a statute in any state. But because name change is controlled by a bureaucratic process, what actually occurs in courthouses across the country on a case-by-case basis can vary wildly. “So much of what happens in this area is informal,” said Columbia Law School professor Elizabeth Emens, who’s written extensively on name change law, “which is what led me to the concept of what I called ‘desk clerk law.’ That’s law as defined by the whims or views of the person at the desk.” Such “law,” she said, “can encompass clerks inserting their normative views or just making mistakes about what the law is,” such that an official form, like the one I was handed, meant to prevent kidnappings, disappearances and fraud, gets prophylactically foisted upon everyone seeking a name change. “It doesn’t mean that the desk clerk is making the formal law,” Emens said, “but just that, effectively, for the person on the street, the desk clerk has determined their choices.”

In other words, bureaucracies in this country were already ill-equipped years before our “ketamine-fueled jester” fed our government into the wood chipper. If reclaiming my name back in 2017 stole weeks of my life and chunks of my sanity—not to mention all the hours of filing paperwork and waiting in a courthouse for a judge to finally rule in my favor—imagine what will happen in 2025 when H.R. 22, the so-called SAVE act, goes into effect.

If you haven’t already heard about it, the SAVE act, proposed by Republican Chip Roy (TX-21), requires American citizens to provide documentary proof of U.S. citizenship to register to vote in federal elections.

What counts as documentary proof of citizenship, according to this proposed bill? Either a Real I.D. or a U.S. passport, if you have one. Alas, 44% of drivers licenses in the U.S. are not Real ID compliant, and more than 140 million American citizens do not have a passport. Should you only be in possession of a regular drivers license, you will be required not only to bring your original birth certificate, in person, to register to vote with that drivers license, but for the last name on that license to match the last name on your original birth certificate.

You know whose last names on their drivers licenses don’t match the last names on their birth certificates? 69 million married women in this country who took their husbands’ last names. My 81-year-old mother, for example. And nearly every single one of her friends.

I, too, was once one of those 69 million women. Not because I took my ex-husband’s name when we got married but because, out of frustration after my first child was born, when our differing last names kept being a bureaucratic thorn in my side, I reluctantly yielded my name for my child’s. Back then, in 1995, I had no idea that, while changing my name to my married name would be relatively easy, changing it back would be straight out of a dystopian fiction that pales in comparison to the one that will be faced by American women who want to vote, should H.R. 22 pass.

The first time I became aware of H.R. 22’s sneaky theft of the America’s female vote—not to mention the low-income, racial minority, and elderly citizen vote—was from this social media post of a Republican town hall, where a woman confronted a smarmy, smirking congressman, Representative Rich McCormick, with the realities of his sexist proposal:

You can click here to read much more about the horrors of this proposed bill to anyone born with a uterus, or disabled, or poor, or a minority. It also has this recent update, that had my jaw on the floor, given that the bill proposes either a passport or Real ID as a form of proof of citizenship, but the latter…doesn’t count?:

The legislation states that “a form of identification issued consistent with the requirements of the Real ID Act of 2005 that indicates the applicant is a citizen of the United States” can be used to prove citizenship. However, the Real ID Act of 2005 does not include a federal requirement for Real IDs to indicate citizenship status, and no state’s Real ID indicates citizenship status on the card. Legally residing noncitizens can also get a Real ID. As it stands, this is an unworkable provision of the legislation, unless the standard for Real IDs is federally changed.

Suffice it to say, I’ve urged my daughter, who’s getting married this May, not to change her name if she ever wants to vote again.

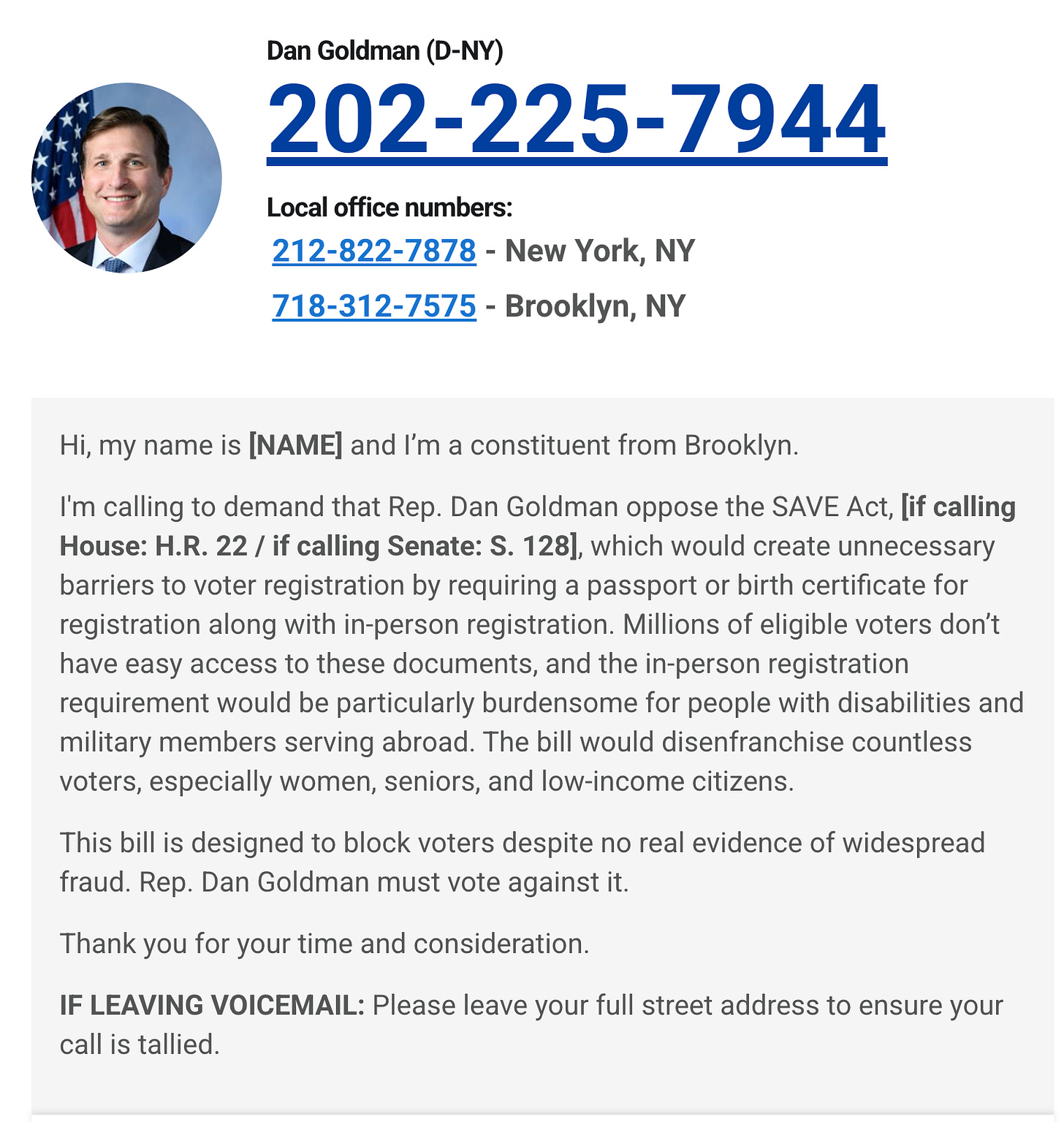

Anyhoo, ladies, let’s make some more calls, shall we? That link goes to the homepage of my new favorite app, 5 Calls, which can help you protest all the important rights you are quickly losing, but here’s a handy-dandy, super easy, specific link for the voter-suppression legislation in question. Here’s what I see when I click on it from Brooklyn:

For now, to counterbalance this sexist madness, all we have is our voice. But if this bill gets passed, many of us will have lost that as well.

My Washington Post Op-Ed from September 28, 2017

I did not want to change my name when I got married in 1993, so I didn’t. But two years later, a postal clerk refused to give me the baby gift I’d come to pick up because my infant son’s last name was different from mine. The address on the package and the address on my driver’s license were identical. The baby, after a long wait in a post office line, was apoplectic. I was told I had to return to the post office with my child’s birth certificate or I could not have the package. Or any future packages sent to him or any future children, for that matter.

Fueled with frustration and postpartum hormones, I scurried down to the Social Security Administration office that same afternoon to change my name. It was as simple an act as it was rash: I handed the clerk my marriage license and a few other forms of ID, breast-fed the baby, and five minutes later I had my husband’s name in lieu of my father’s. I wasn’t thrilled about the change, and I then had to jump through the logistical hoops of notifying the DMV, the passport office, my bank, my employer, et al. But it was as easy to rationalize as it was to effectuate: For the sake of bureaucratic convenience, I was trading one man’s surname for another’s. At least I could now pick up my children’s packages at the post office and fly alone with them to foreign countries without presenting birth certificates to postal clerks and border-control agents. Right?

Twenty-two years later, I was nearly four years separated, and I tried to change my name back to its original version. I went to the DMV, where I was told I needed a divorce decree, which I didn’t yet have. The other option, the clerk said, was to petition a judge for a name change and pay a $65 fee, which, with the divorce dragging on, is what I decided to do.

“Are you still married?” asked the clerk handing out blank forms in civil court. Officially, yes, I told him, which is when he handed me a second form that my ex had to fill out and notarize to give me permission to have my name back.

“Permission?” I said, louder than might have been considered polite. “That is unbelievably backward and sexist.”

“No,” snapped the clerk, “it’s not. Men have to do it, too.”

“Right. All those men who need to change their names back from their married names to their maiden names. You must be flooded with such cases.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ladyparts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.