What to expect when you're unsuspecting

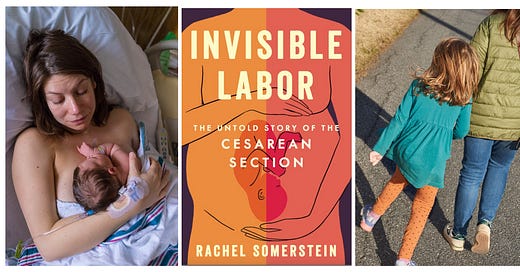

Eight years ago, Rachel Somerstein was wheeled in for an emergency c-section. "I felt that!" she called out, with the first slice into her abdomen. But no one listened.

A few years ago, I was invited up to SUNY New Paltz to give the 2021 Ottaway lecture. Earlier in the day, as part of my pre-lecture responsibilities, I taught several classes of students, one of which was normally taught by Professor Rachel Somerstein, who told me about her ongoing research into the c-section. What was there to know, I wondered, about t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ladyparts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.